Hurricane Katrina+20, Part 1: The Fading Watermark

'Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real.' Cormac McCarthy

August 29, 2025, marks the 20th Anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s landfall. Part One of a two-part series on this significant milestone looks at the compassion fatigue and apathy that grew during the city’s recovery.

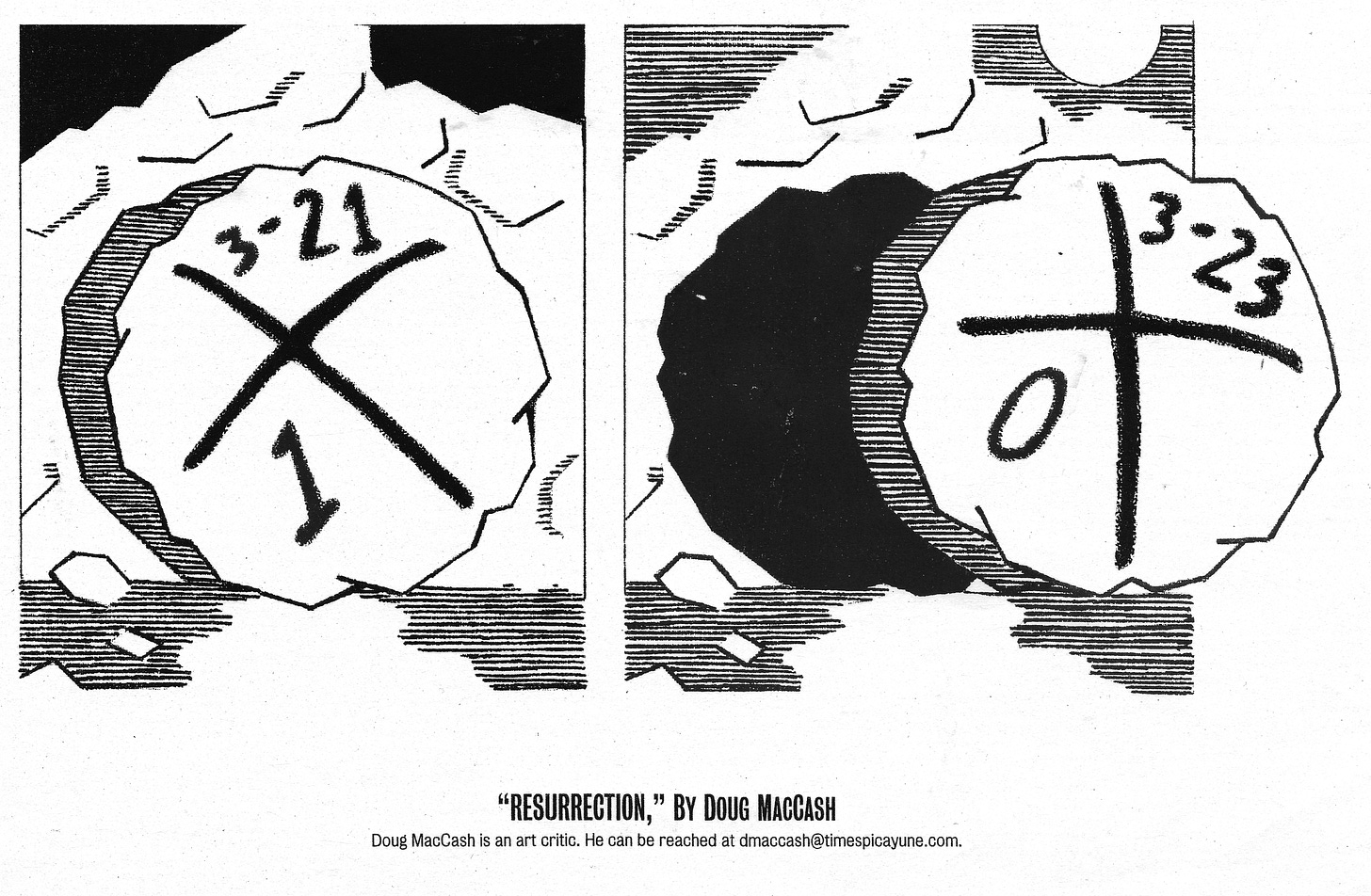

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, every house and building in New Orleans bore the scars of the monster storm. Along with the roof, structural, and tree damage from wind, two marks marred almost every structure in town—the giant spray-painted “x” applied by search and rescue teams and the watermark left by the rising floodwaters that refused to recede.

The “x” mark included the date that a structure was searched, along with the number of dead found there. Thankfully, the vast majority of these “x” marks listed zero dead. In the aftermath and recovery, New Orleanians often embraced the rescue “x” as a symbol of survival. Some even had bronze copies of their “x” recreated before painting over the one sprayed by rescuers. These serve as a constant reminder of resilience and love for the city.

Watermarks marred every structure as well. But watermarks also stained trees, retaining walls, wrought-iron fences, light poles … everything. Even the vast cities of the dead - the cemeteries full of aboveground tombs and mausoleums throughout the city – bore the marks. Levee failures left New Orleans filled with water, scarring every structure (and all of us who lived in the city at the time).

Nothing in New Orleans bore only one watermark. Each tree, rock, wall, and building wore a series of watermarks. One prominent muddy brown line marked the high-water mark of the flooding. Rather than quickly emptying, the flood waters remained high for many days—adding to the staying power of that line. Along with the prominent watermark were fainter lines marking the water level positions as the floodwaters were slowly pumped out of the city.

These marks survived for years before gradually fading away. A few persist even today. However, the watermark never reached the symbol status achieved by the search and rescue “x”.

The Watermark as a Metaphor

For me, the fading watermark serves as a compelling metaphor for the storm’s ongoing aftermath. I have often thought to myself that Katrina left a figurative watermark all the way up to my heart—a scar, if you will. I liked New Orleans before the storm. I found the city fun and intriguing. After the storm, love for the city flooded over me. I wanted to help her recover. Even today, I passionately defend New Orleans even though I know all her flaws. We (New Orleanians) can talk about New Orleans and our frustrations with our government, but we will push back on your critiques. We bear marks from the storm and scars from unmet expectations. Despite all of the government deficiencies and humidity, the city rewards us with food, Jazz, Mardi Gras, and snowballs.

Apathy Rose as the Watermark Faded

One oft-quote line from Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses comes as two characters discuss the scars they bear. One character states: “Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real.” This is so true … one positive aspect of these reminders of hurtful events. I have four large scars on my arm left by our old gas heater. I “earned” these scars when I fell against the stove one cold Sunday morning. I was dancing because I was excited to go to church when it happened. I was very young, and I don’t remember the actual event. But I still carry the scar and still recount how I received it from time to time. In grade school, the scar was quite pronounced and visible. People asked about it. I could feel it when I rubbed my arm. I thought about it quite often. But the scar fades more and more each year. Now it is barely visible, and I rarely think about it.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, we came together as a city. We rallied. We worked together. We loved our neighbors. People gave up their Saturdays to help others gut their homes and rebuild. Christians put Jesus’s teaching into daily practice by loving in word and deed. Believers experience a renaissance of creative ideas and address important issues with compassion and the Gospel. And we praised God for the opportunity to serve Him in this way, even though we hated the storm.

Those first 5-6 years were difficult. The infrastructure was broken, and stores were slow to reopen. I believe it took about four years to get all the traffic lights working on Gentilly Blvd. Slowly, the city improved. We worked hard on our public schools. We helped the underserved and looked for ways to give them a “hand up.” We came together across racial and political lines. WE WON A SUPERBOWL (okay, the Saints won it, but we felt like we played a role)!

What happened to the love, unity, and creativity that fueled our recovery? Time and exhaustion took their toll. Caring is difficult work. Perhaps the physical reminders got lost in the sea of competing patinas that give our old building character. Perhaps we cleaned up so many physical scars that we began overlooking the emotional ones. All the togetherness and love began to fade like the watermark left in the storm’s wake (or the burn lines on my arm). New wounds appeared – the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, growing division in national politics, racial unrest/removal of Confederate monuments, COVID, other tropical storms and hurricanes, astronomical home insurance rate increases, the January terrorist attack, and more. These fresher wounds captured our attention. Cultural fault lines that predate Katrina began to reappear.

‘Living is Easy with Eyes Closed’

In “Strawberry Fields Forever,” The Beatles sing an unforgettable truism: “Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.” Life is much easier when you look out for yourself and ignore the problems around. Some of us in New Orleans began to close our eyes to the needs. To escape. To attend to the concerns of life. We had given so much of our lives to the recovery. We needed a break. We had to make money, care for our families, pursue education, and pursue our own leisure. Over time, it became easier to ignore the growing issues in the city as we went about our daily lives. Some of us have spent more time playing in New Orleans in recent years than serving in it. How can I get back to the days when I praised God for the opportunity to give myself away to reach the city?

I Miss that New Orleans

Louis Armstrong’s “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans” became a favorite song during the eight months we spent in Atlanta after the storm. We longed to be home. We longed for the pre-Katrina New Orleans. That (along with prayer and calling) carried us through until we returned. But, I don’t really miss the pre-Katrina New Orleans anymore. The New Orleans I miss is the one we forged in the first 5-9 years after the storm … the one where we loved one another well and sought the well-being (the shalom) of the city (Jeremiah 29:7). How do we get back to that New Orleans?

Writer’s note: Katrina+20 Part 2 is coming soon. I promise to focus more on hope in Part 2.

I enjoyed the perspective you brought to this. Something I’ve not seen before.